26 May 2025

Brazil’s avian influenza: what does it mean for Malaysia?

Brazil has confirmed a HPAI outbreak on a commercial poultry farm, raising global concern. Could this development impact poultry supply or biosecurity in Malaysia?

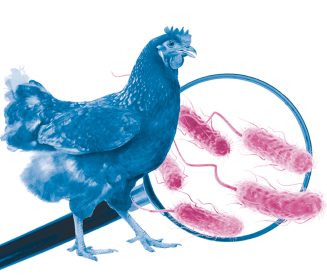

The recent confirmation of a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak at a commercial poultry farm in Brazil—the world’s largest chicken exporter—has triggered concern across global markets.

Could this outbreak ripple across the globe and affect poultry supply or biosecurity in Malaysia?

While Malaysia imports relatively small volumes of chicken from Brazil, experts say no country is immune to the impact of global disease outbreaks, especially in an interconnected food system.

Minimal direct trade, but no room for complacency

Malaysia imports most of its poultry from neighboring countries, including Thailand and China, while also maintaining substantial domestic production.

Brazil is not a key supplier in the Malaysian poultry trade matrix. However, global market reactions—such as trade bans and redirection of shipments—can create indirect shocks.

For example, when major buyers like China, Japan, and the EU suspend poultry imports from Brazil, it could increase demand on other exporting nations. This can tighten global supply and lead to price hikes, even in countries not importing directly from Brazil.

Moreover, international poultry trade is deeply interlinked. Feed ingredients, hatching eggs, or even frozen [chicken meat] stocks might be indirectly routed through third-party countries.

In this scenario, Malaysia’s food safety protocols must remain vigilant in tracing and containing any potential entry points of disease.

The risk is more than economics—it’s biosecurity

The more urgent concern is not price volatility but biosecurity risks.

HPAI is more than a poultry disease; in rare cases, it can infect humans who come into close contact with infected birds or contaminated surfaces.

Malaysia’s Department of Veterinary Services and the Ministry of Health have strong surveillance and early warning systems in place. However, as Brazil’s outbreak shows, even top-tier poultry-exporting nations can face unexpected challenges.

In Brazil’s case, the virus spread from wild birds to a commercial farm for the first time in May 2024. By then, over 17,000 chickens had either died or were culled, and 450 tons of eggs were destroyed. The incident prompted urgent containment measures and global scrutiny.

Why surveillance is everything

Malaysia’s frontline defense is disease surveillance—monitoring both domestic farms and import channels.

Early detection allows the government to implement targeted bans, activate contingency protocols, and avoid widespread economic or public health fallout.

Proactive surveillance also reassures trade partners and consumers. As part of ASEAN and World Organization for Animal Health, Malaysia must uphold international standards in controlling zoonotic threats like avian influenza.

“Surveillance isn’t just about detecting disease—it’s about preserving confidence in our food systems,” a food safety officer from the Ministry of Agriculture said.

Conclusion

Although the avian flu outbreak in Brazil may not directly affect Malaysia’s poultry supply, the lesson is clear: in a globalized food economy, disease outbreaks halfway around the world can still rattle local markets.

Malaysia’s continued investment in strong surveillance, import regulation, and rapid response protocols will be critical—not just to protect poultry, but to maintain public health and food security in an increasingly unpredictable world.