Available in other languages:

Content available at: When fly populations are not properly controlled, they can become a public health problem in nearby poultry farms and rural non-farm communities, often leading to poor community relations and potential litigation2.

Español (Spanish)

Flies also negatively affect productive performance as a result of the stress they generate in animals. In the case of a heavy infestation, the birds can be overwhelmed, drastically reducing their feed intake, consequently reducing meat and egg production3.

Flies defecate and regurgitate, staining structures and equipment, lighting fixtures – reducing the level of illumination – and eggs – posing a risk of pathogen transmission in newly laid eggs, which reduces their attractiveness in the eyes of the consumer as well as their market value3 -.

Scientists have calculated that a pair of flies that start breeding in April have the potential, under optimal conditions, to spawn up to 191,010,000,000,000,000,000 flies in August1.

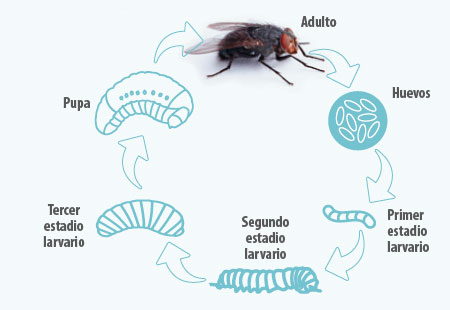

Figure 1. Life cycle and characteristics of the house fly.

Development

Fly eggs hatch into larvae in the brooding areas before pupating and eventually develop into adults to repeat the life cycle throughout the season. The development cycle, population density, and daily activities of these flies include flying in a particular area based on resources, temperature, and other biotic and abiotic factors. When food is not limited, flies complete their life cycle in approximately:

Flies produce multiple generations per year that can coincide, and all stages of development can be found at the same time. Although development is temperature dependent, it is possible for multiple generations to appear per year in tropical and temperate zones due to peridomestic habits3.

Displacement

Different studies have shown that flies can travel distances ranging between 3.22 km and 32.19 km. Their flights are aimed at looking for food and oviposition sites, considering flies travel more in rural areas than in urban areas due to the fact that human settlements are more dispersed. At night the flies are normally inactive3.

Feeding

Both males and females eat all kinds of food of human and animal origin, garbage and excrement. Liquid food is ingested by suction and solid food is moistened with saliva to dissolve it before ingestion.

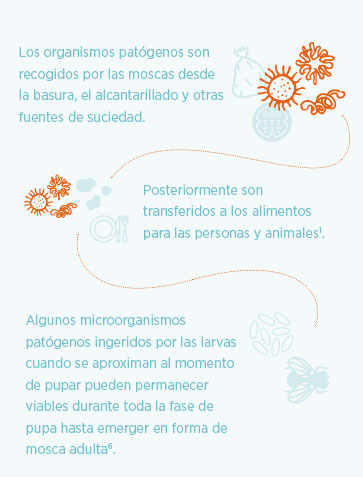

The house fly is an important vector for many human and poultry diseases – protozoa, bacteria, viruses, rickettsiae, fungi, and nematodes1 – and can cause spotting problems on eggs, as well as on building windows2 .

Antimicrobial resistance

Fly control could be seen as a way to reduce the spread of diseases on farms, while also minimizing the need to use antibiotics to treat said diseases. Flies carry and spread antibiotic resistant bacteria, both on farms and in hospital settings3. Therefore, controlling them is one way to reduce the spread of resistant bacteria.

Musca domestica species have been indicated as a mechanical transmitter of pathogens such as the paramyxovirus that causes Newcastle disease 7, Avian Influenza virus during periods of 72 hours after infection8, as well as bacteria, such as Shigella spp., Vibrio cholerae, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp.9, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Aeromonas spp.10, Campylobacter spp., As well as protozoan parasites and eggs of some cestodes7.

Subscribe now to the poultry technical magazine

AUTHORS

Layer Longevity Starts at Rearing

H&N Technical Team

The Strategy for a Proper Infectious Bronchitis Control

Ceva Technical Team

Elevate Hatchery Performance with Petersime’s New Data-Driven Incubation Support Service

Petersime Technical Team

Maize and Soybean Meal Demand and Supply Situation in Indian Poultry Industry

Ricky Thaper

Production of Formed Injected Smoked Chicken Ham

Leonardo Ortiz Escoto

Antimicrobial Resistance in the Poultry Food Chain and Novel Strategies of Bacterial Control

Edgar O. Oviedo-Rondón

GREG TYLER INTERVIEW

Greg Tyler

Insights from the Inaugural US-RSPE Framework Report

Elena Myhre

Newcastle Disease: Knowing the Virus Better to Make the Best Control Decisions. Part II

Eliana Icochea D’Arrigo

Avian Pathogenic E. coli (APEC): Serotypes and Virulence

Cecilia Rosario Cortés

The Importance of Staff Training on Animal Welfare Issues in Poultry Industry

M. Verónica Jiménez Grez

Rodent Control is a Key Factor in Poultry Biosecurity and Sustainability

Edgar O. Oviedo-Rondón