Content available at: Indonesia (Indonesian) ไทย (Thai) Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese) Philipino

Infectious Bursal Disease Virus Variants: A Challenge for Commercial Vaccines?

Gumboro disease, also known as Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) or Avian Infectious Bursitis, was first reported in Delaware, USA, in 1962. It is an immunosuppressive viral disease that primarily affects chickens between 3 to 6 weeks of age and has a global distribution.

- The virus responsible for this disease belongs to Avibirnavirus genus, Birnaviridae family, and has two serotypes: I and II.

- Serotype I has been detected in chickens, hens, pigeons, and guinea fowl (Kasanga et al., 2008) but is only pathogenic in chickens and hens.

- Serotype I is further divided into two antigenic subtypes: classical and variants, while serotype II remains asymptomatic in turkeys, crows, ostriches, and ducks (Ogawa et al., 1998; Yilmaz et al., 2019).

Since its first report, numerous variants of the virus have been identified, complicating efforts to control the disease. Until the 1980s, vaccination was effective in control the disease, with mortality rates in broilers below 2%.

However, with continued mutation and reassortment of the virus, new antigenic variants emerged, leading to higher mortality rates, even in the presence of strict vaccination protocols.

These variants can appear subclinically, reducing growth and increasing susceptibility to secondary infections, which result in substantial economic losses for the poultry industry.

ZOOMING INTO THE VIRUS

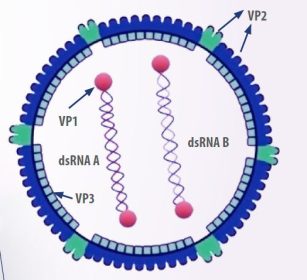

- The virus has an icosahedral shape, no envelope, and consists of two linear double-stranded RNA segments, designated as A and B.

Segment B encodes VP1, a viral polymerase RNA, while segment A produces the capsid proteins pVP2 and VP3, as well as the protease VP4 and VP5, a non-structural protein involved in regulatory functions and membrane disruption in infected cells (Mundt, 1999) (Figure 1).

Among the components mentioned above, the VP2 protein is particularly important as it determines the virus’s antigenicity, virulence, and pathogenicity. It contains regions that antibodies can bind to, and when exposed to the immune response, it tends to undergo greater mutation, making it a highly variable region (Letzel et al., 2007).

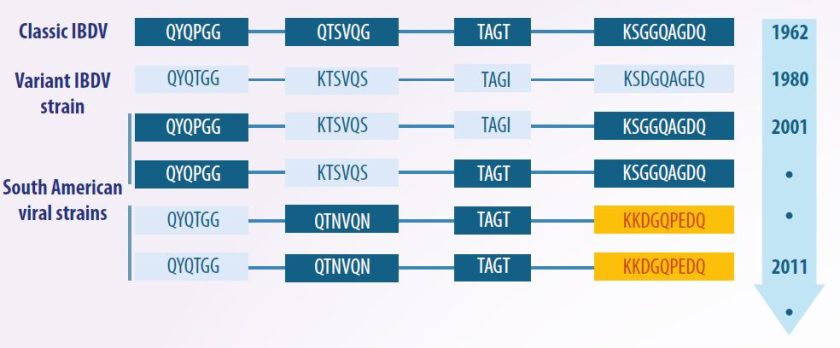

- The capsid protein VP2 contains three distinct domains: base (B), envelope (S), and projection (P).

- The P domain is made up of four loop structures exposed on the virus surface.

- The Pbc loop (amino acid positions 219 and 224) plays a role in stabilizing the antibody recognition site.

- The Phi domain (amino acids 315–324) is recognized by neutralizing antibodies and is the primary site for amino acid substitutions that enable the virus to evade the immune response.

- The remaining two loops, Pde (amino acids 250–254) and Pfg (amino acids 283–287), are associated with the virus’s ability to cause disease (Jackwood et al., 2018) (Figure 2).

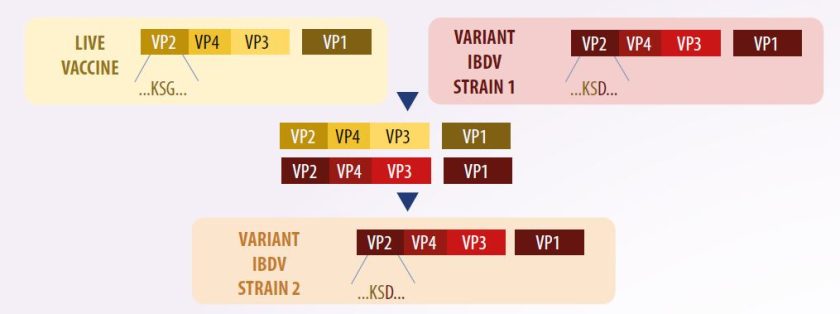

In addition, the segmented nature of the virus genome facilitates genetic reassortment between strains during co-infection. For example, this allows a live vaccine strain and a wild-type virus to mix. As a result, mutations and reassortment contribute to antigenic variability, which can reduce the effectiveness of commercial vaccines against the disease, leading to significant challenges in disease control (Gao et al, 2007).

ADVANCEMENTS IN VIRUS CLASSIFICATION SCHEMES

- Since its first identification in 1962, strains were not categorized, as they were assumed to be similar in both antigenicity and pathogenicity.

- However, in 1980, the discovery of serotype 2 led to the identification of antigenic variants, referred to as “variants”, as well as highly virulent strains, known as “very virulent strains” (vvIBDV).

- As a result, the strains detected prior to these variants were classified as “classical strains”.

- Alternative methods were used to name strains, based on the name of the scientist who first characterized the isolate (e.g., Winterfield, Lukert, Moulthrop, Baxendale), the location of the isolate (e.g., Del-A, Del-E, MD, OH), or alphanumeric codes (e.g., STC, D78, G603, S706, 228E).

However, over time, characteristics related to the antigenicity, molecular structure, and pathogenicity of these categories were discovered. This led to a traditional classification scheme, which divides strains into classical and variant, with the latter further subdivided into attenuated, virulent, and very virulent categories.

Regarding the genome, vvIBDV share specific amino acid residues at positions 222 (Ala), 256 (Ile), 294 (Ile), and 299 (Ser) in the VP2 sequence. In terms of pathogenicity, compared to classical strains, vvIBDV tend to cause higher mortality rates in specific pathogen-free chickens upon infection (Van Den Berg et al., 2004). However, not all very virulent strains exhibit high pathogenicity, indicating that this classification is incomplete (Jackwood et al., 2018).

- Subsequently, due to ongoing mutations and recombinations, new strains could not be classified using the traditional system.

- As a result, Michel and Jackwood (2017) proposed a new classification based on the amino acid sequences of the hypervariable region of VP2. This approach led to the identification of 7 genogroups.

- However, these genogroups did not account for new variant strains or attenuated strains.

- Furthermore, due to the characteristic recombination of viral segments, a classification based solely on VP2 did not fully capture the complexity of the virus’s genogroups.

In 2021, Wang et al. proposed a new classification system that considers the molecular characteristics of VP1 and VP2, derived from the B and A segments, respectively.

- This approach resulted in the identification of 9 genogroups for segment A and 5 genogroups for segment B.

- Notably, genogroup A2 consists of 4 distinct lineages.

- In this new classification, the genotypes A1B1, A2B1, A3B2, and A8B1 correspond to the classical, variant, highly virulent, and attenuated phenotypes, respectively.

PATHOGENESIS AND CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS

In its typical pathogenesis, the IBDV enters the body through the respiratory or fecal-oral routes, where it initially replicates in macrophages and lymphoid cells in the intestine or surrounding areas.

- This initial replication triggers primary viremia via portal circulation, allowing the virus to reach its main target organ, the bursa of Fabricius.

- Within the bursa, the virus actively replicates in follicles and B lymphocytes, which are actively dividing in young chicks.

- The infection causes degeneration and necrosis of the follicles, mainly affecting IgM+ B lymphocytes, and leads to the infiltration of heterophils.

- These heterophils eventually undergo necrosis and are phagocytosed.

- In the interfollicular areas, hyperplasia of reticuloendothelial cells is observed, resulting in progressive atrophy of the bursa (Müller et al., 2012).

- Although the virus does not replicate in T lymphocytes, apoptosis of these cells is observed in the thymus, with recovery of microscopic lesions occurring days after infection (Jagdev et al., 2000).

- Regarding secondary viremia, it begins approximately 11 hours after replication in the bursa.

- During this phase, the virus enters the bloodstream and spreads to the kidneys, muscles, and other organs, leading to clinical signs such as depression, ruffled feathers, anorexia, and diarrhea.

- In severe cases, this can result in the death of the animal (Eterradossi & Saif, 2008).

The virus stimulates B lymphocytes, increasing the expression of antiviral genes in the type I interferon (IFN) pathway, proapoptotic genes, and proinflammatory cytokines. In addition, the VP2 and VP5 proteins induce apoptosis in B lymphocytes and other lymphoid cells. During viral replication, there is a significant infiltration of T lymphocytes into the bursa, which persists until approximately 12 weeks post-infection.

- From day 7 post infection, CD8+ (cytotoxic) T-lymphocytes outnumber CD4+ T-lymphocytes in proportion to CD4+ T-lymphocytes.

- This increase in CD8+ T lymphocytes promotes cell killing by lysing cells that express viral antigens and by producing proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ.

- This cytokine triggers the release of nitric oxide by macrophages, increasing bursal tissue damage (Jagdev et al., 2000) and contributes to immune cell exhaustion.

Virus variants induce elevated levels of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, NLRP3, caspase 1, and TNF-α, promoting inflammation and altering the tissue microenvironment. This strategy suppresses B-lymphocyte activity, enabling the virus to evade immune responses, resulting in increased bursal damage and more severe immunosuppression compared to classical strains (Jagdev et al., 2000; Li et al., 2023).

- For instance, Li et al. (2023) demonstrated that the vvIBDV exhibits high pathogenicity, enhanced replication efficiency, and a significant capacity to damage the bursa and other tissues, leading to high lethality.

- This strain spreads to the bursa, cecal tonsils, thymus, and spleen, and alters cytokine levels within the bursa.

- In contrast, the SHG 19 variant from China, reported in 2020, exhibited reduced replication and did not cause mortality but still caused severe immune organ damage similar to the vvIBDV.

- This variant caused extensive necrosis and disintegration of B lymphocytes, though these changes developed more slowly—approximately 12 hours later than with the highly virulent strain.

- This delayed mechanism may contribute to the variant’s ability to excrete externally, potentially allowing it to become a dominant epidemic strain (Fan et al., 2020).

CHALLENGE FOR COMMERCIAL VACCINES

Vaccination with genotypes different from wild-type viruses can lead to genetic diversity among circulating virus strains. In such cases, reassortment may occur—such as between a very virulent A segment and a B segment from a classical strain—resulting in mortalities of up to 80% in chickens with acute bursal lesions (Pikuła et al., 2018) (Figure 3).

Moreover, the antigenic distance between the wild-type virus strain and the vaccine strain means that variants may not be effectively controlled by conventional serotype 1 vaccines. Therefore, it is now recommended that vaccine production against IBDV include antigenic mapping, a computational method used to determine the antigenic distances between strains. This technique has already been successfully applied to equine and human influenza viruses. On the other hand, it is important to assess cross-protection during the vaccine development process to ensure efficacy (Boudaoud et al., 2016).

CONCLUSION

- IBD remains a significant challenge for the poultry industry due to the virus’s rapid mutation, genetic reassortment, and the emergence of new, highly virulent variants.

- These variants contribute to severe immunosuppression, high mortality rates, and increased susceptibility to secondary infections, despite vaccination efforts.

- The virus’s genetic complexity, particularly in the VP2 protein, complicates effective vaccine development, as antigenic variability can undermine vaccine efficacy.

- The ongoing evolution of the virus calls for more sophisticated strategies, such as antigenic mapping and cross-protection assessment, to improve vaccine design and enhance control measures against this economically impactful disease.

*References upon request to the author