Content available at: Español (Spanish) Português (Portuguese (Brazil))

Vaccination is generally considered to be the most important process that results in immune protection of a flock. However, the current understanding of immune principles implies that other management processes are highly relevant in improving productivity through the control of immunity.

Population immunity implies: Investing in nutritional quality, rational use of performance additives, use of antibiotics, biosecurity, staff training and well-structured vaccination protocol.

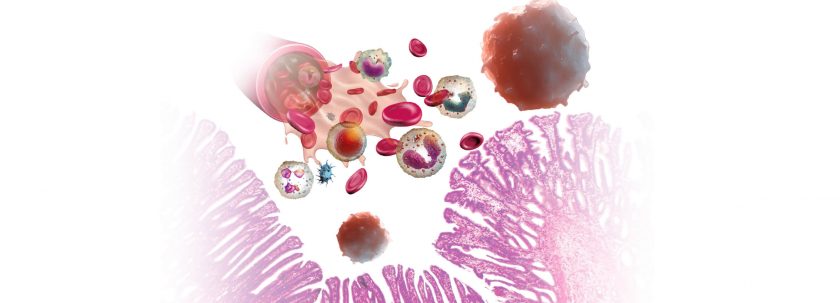

The mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) is highly developed. The intestinal component of this system is the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), which corresponds to 80% of all MALT and is composed of a complex organization of primary and secondary lymphoid organs. Peyer’s patches (organized lymphoid tissues present in the intestinal wall) are made up of B lymphocytes, most of which secrete IgA into the intestinal lumen.

Young birds have approximately six PPs, which, like other lymphoid components, become involuted with age. In later stages of life, only one intestinal lymphoid aggregate can be found. Tonsils and PP are easily identifiable in 10-day-old chickens that reach their maximum development between 5 and 16 weeks of age. With natural age-related involution, these intestinal immune tissues may not be visible at 20 weeks.

At 53 weeks only a single Peyer’s plate remains. Although the constitution of PP closely resembles that of pigs, birds also have a unique lymphoid aggregate, Meckel’s diverticulum.

It is the residual yolk sac that shows germinal centers with B lymphocytes and macrophages. The intraepithelial lymphocyte population in the diverticulum increases 3 to 5 times 5 days after incubation and up to 10 times at 14 days and even more until 40 days of age. In poultry, immune cells in the intestines do not cluster exclusively in lymphoid tissues. The intestinal mucosa, made up of the epithelium and the lamina propria, is also rich in leukocytes.

These lymphocytes are present in the intestine at the time of hatching, since they have already colonized it from approximately 16 days after incubation. Between 4 and 6 days of life this colonization increases and reaches maturity in the first two weeks of life. The processing of foreign materials (antigens) by the GALT follows a sequence similar to that of systemic lymphoid tissues. However, in GALT enterocytes, they also play a role in transporting molecules from pathogens to the reaches of the immune cells. In the intestinal epithelial lining, M cells are crucial in accomplishing this task. Both enterocytes and M cells will contribute to the defense against pathogens.

Local intestinal architecture often undergoes changes in response to pathogens, such as disturbances in crypt depth, mucus production, lymphoid cell infiltration, increased cell spacing, and so on. More specific responses will be constructed in Peyer’s patches, where B lymphocytes will initiate IgA responses directed against the pathogen.

After a pathogen invasion, many structural changes occur in the gut, related to permeability, cell infiltration, crypt enhancement, mucus and enzyme production, in addition to specific antigenic responses. The specific responses to pathogens, called the adaptive immune response, involve two main types of cells:

- B lymphocytes, which express surface immunoglobulins, and react with the production of different antibodies (humoral immune response).

- T lymphocytes, which recognize the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) -antigen-MHC complex, presented on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (macrophages, dendritic cells, and eventually even enterocytes).

TO CONTINUE READING REGISTER IT IS COMPLETELY FREE Access to articles in PDF PDF

Keep up to date with our newsletters

Receive the magazine for free in digital version REGISTRATION ACCESS

YOUR ACCOUNT LOGIN Lost your password?