Content available at: Indonesia (Indonesian) ไทย (Thai) Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

Fatty liver hemorrhagic syndrome (FLHS) is one of the leading causes of mortality for laying hens, mainly those housed in cages. This disease is observed mainly in hens in the middle and late stages of egg production.

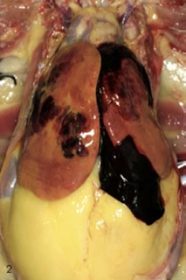

- During a post-mortem examination, severe fat buildup is noticed in the abdominal cavity and the visceral areas.

- The liver is swollen, spherical, and extremely delicate or fragile.

- Due to fat accumulation, its color changes from pale brown to yellow.

- This condition commonly results in liver rupture, hemorrhages, and unexpected mortality due to internal hemorrhages.

It is relevant to remember that death from FLHS occurs only in extreme cases following massive liver hemorrhage, suggesting that a significant number of hens within a flock might suffer from “sub-acute and chronic FLHS”. The chronic form of FLHS may cause a drop in egg production but little or no change in mortality. These hens may show reproductive dysfunction.

In 2021, researchers from Hebei Agricultural University in China concluded that liver metabolites and arachidonic acid metabolism were linked to the pathophysiology of FLHS. Hens with FLSH have significantly higher levels of metabolites like alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, low-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, and triglycerides, decreased high-density lipoprotein, and hepatic steatosis.

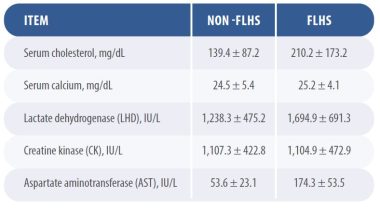

The FLHS causes profound changes in liver function that can be detected by blood tests (Table 1).

- In the layers with FLHS, liver carnitine and stearoyl carnitine are reduced.

- As an essential factor in fatty acid metabolism, carnitine plays a key role in fatty acid transportation into mitochondria for oxidation.

- The conditions of fatty liver disease promoted fatty acid oxidation to provide energy, accompanied by carnitine consumption.

Environmental factors that increase incidence

Data from diverse surveys and controlled studies worldwide have revealed that housing systems do not affect mortality rates or that mortality rates are lower in conventional cage systems than in free-range or organic systems. However, the cause of death is well related to the cage system. The most common cause of death in conventional cages is FLHS, with 58 to 74% of necropsied hens dying from this condition.

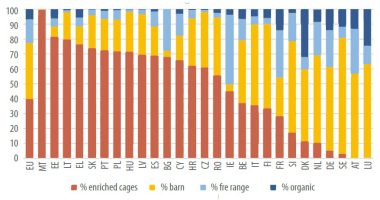

- Conventional cage systems have decreased worldwide due to welfare concerns and governmental regulations, but they are still the predominant housing system worldwide.

- Their utilization varies between continents and countries.

- After 12 years of the conventional cage ban in the European Union, the replacement with “enriched cages,” and 6 years of the campaign “End the Cage Age,” the laying hen housing systems are expected to be distributed as described in Figure 1.

In 2018, it was reported that more than 90% of egg production in three of the largest egg-producing countries (China, Japan, and the United States) comes from caged hens. This figure is nearly 98% for the other four largest egg-producing countries (Turkey, India, Russia, and Mexico). In Australia (2024), approximately 50% of eggs are produced in cage layer farms, with the balance coming from free-range (40%) and barns (8.5%).

- The proportion of hens housed in conventional cage systems is expected to be lower now, with multiple large egg-producing companies in these countries adopting other housing systems.

- However, the data indicates cage systems are still very important, and the associated disease issues, such as FLHS and cage fatigue, are still very relevant.

Multiple studies’ data indicate that increased body weight and high production of laying hens in conventional cages significantly increased mortality, in many cases, associated with fatty livers and FLHS.

- Recent research has confirmed that hen metabolism is modified by housing.

- Last year, María Herrera-Sanchez and collaborators from the University of Tolima in Colombia published a paper in the Journal of Veterinary Medicine International suggesting that differential expression of genes related to oxidative stress in liver tissues from hens housed in conventional cages compared to cage-free systems.

This study indicated that space and environmental conditions in the egg production system could impact the expression of oxidative stress and lipid synthesis genes, potentially leading to changes in hens’ metabolism and performance, including egg quality and the incidence of metabolic diseases like FLHS.

- The conventional cage system may not allow sufficient movement and exercise for hens, mainly when high stocking densities are used.

- Reduced exercise can affect muscle and bone metabolism, leading to systemic metabolic changes.

- One of the main characteristics of FLHS is insulin resistance, which leads to lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and the inflammatory cascade that causes cirrhosis and fat infiltration in the liver.

- Flocks housed in “enriched” or “furnished” cages that provide more space, perches, nests, and a scratch area have lower FLHS incidence.

Generally, conventional cage housing and high stocking densities are highly associated with FLHS. However, elevated ambient temperatures, high humidity, low ventilation, and poor air quality can increase the incidence of FLHS. A high body temperature inhibits the thyroid gland’s ability to secrete thyroid hormones and weakens lipolysis, which are risk factors for developing fatty liver disease. Immunological challenges from field pathogens or vaccines can also increase FLHS incidence.

Nutritional factors related to FLHS

The following dietary factors increase the incidence of FLHS in laying hens:

- Unrestricted intake.

- Low protein diets and high energy diets from fat.

- Low levels of linoleic (C18:2 n-6) acid and choline.

The dietary content of linoleic acid should be at least 1.20% during rearing, and hens should consume between 1.40 and 1.60 grams per day during the laying phase. Linoleic acid supplementation could reduce lipid accumulation in the liver and egg of laying hens by regulating the expression of the hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptor and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. Meanwhile, increased biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, linolenic acid, and linoleic acid in hens with FLHS might suggest alterations in lipid metabolism and mobilization of fats from the liver to other tissues.

Choline dietary content should be at least 2,000 mg/kg in the starter phase, 1,800 for the rest of the rearing period, and hens should ingest at least 180 mg/day of choline.

- High levels of mycotoxins like aflatoxins and trichothecenes T2. The median lethal dose (LD50) of T2 for hens is 6.27 mg/kg of body weight. However, this mycotoxin can start causing hen liver damage at concentrations 20 times lower (0.31 mg/kg) after prolonged exposure or when aflatoxins and other mycotoxins are present.

- Hens-fed maize-based diets have higher liver weights, liver fat content, and triglyceride levels 30 to 50% higher, and more livers with hemorrhagic scores related to FLHS than hens-fed diets containing wheat, oats, or barley.

In contrast, the following nutritional factors can prevent or mitigate FLHS:

- Flaxseed, flax oil, and omega-3 supplements decrease hepatic fat content and may reduce FLHS incidence.

- Higher (67%) dietary concentrations of branched-chain amino acids (2.00, 1.08, and 1.17% of Leucine, Isoleucine, and Valine compared to 1.20, 0.65, and 0.70%) inhibit the tryptophan-ILA-AHR axis and de novo lipogenesis, promoting ketogenesis and fatty acid β-oxidation.

Supplementation of the following vitamins and feed additives has shown promising results in minimizing FLHS incidence in laying hens:

- Folic acid (13 mg/kg) positively influences lipogenesis and mitigates endoplasmic reticulum stress and hepatocyte apoptosis.

- Lutein (30 to 120 mg/kg) could prevent FLHS in older laying hens through the modulation of lipid metabolism but, most importantly, antioxidative and anti-inflammatory functions. It also enriches lutein in the eggs, improving the relative redness of the eggs without significant conversion into zeaxanthin or consequence on other physical parameters of the eggs.

- Bile acids (0.01% and 0.02% of chenodeoxycholic acid or hyodeoxycholic acid), regulate lipid metabolism, bolster antioxidant defenses, reduce inflammation, and modulate the gut microbiota.

- Mulberry leaf extract at 1.2% of the diet (polysaccharides 20%, flavonoids 3%, and alkaloids 2%) may regulate the mRNA expression of lipid metabolism-related genes and improve cecal microbiota balance and serum lipid levels to alleviate FLHS in laying hens and subsequently improve egg production performance.

- Cysteamine, the aminothiol agent, at 100 mg/kg of feed in combination with Choline (trimethyl, β-hydroxy ethyl ammonium) at 4,124 mg/kg of feed can ameliorate the adverse effects of FLHS by regulating antioxidant enzyme activities, modulating hepatic lipid metabolism, and restoring production performance in laying hens.

- Magnolol between 100 and 500 mg/kg feed. Magnolol is the primary active component of the plant Magnoliae officinalis. This plant compound inhibits fatty acid synthesis and promotes fatty acid oxidation.

- Poly-dihydromyricetin-fused zinc nanoparticles (PDMY-Zn NPs) resulting from the chemical combination of Zn and Dihydromyricetinat at 200 to 600 mg/kg of feed. This product was reported to alleviate FLHS by enhancing antioxidant capacity, regulating liver lipid metabolism, and maintaining intestinal health. Dihydromyricetin is a naturally occurring flavonoid compound primarily extracted from the traditional Chinese medicinal plant Ampelopsis grossedentata.

- Berberine, a well-known quaternary ammonium alkaloid mainly extracted from various plants such as Coptis and Phellodendron, at 100 or 200 mg/kg alleviated FLHS by reshaping the microbial and metabolic homeostasis within the liver-gut axis.

- Polysaccharides extracted from the plant Hericium erinaceus (250 – 750 mg/kg) ameliorate the hepatic damage by improving intestinal barrier function and shaping gut microbiota and tryptophan metabolic profiles.

- Silymarin, the predominant compound of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) seeds at 200 mg/kg BW, decreased liver weight, malondialdehyde content, expression of fatty acid synthase, and hepatic steatosis.

In the past five years, there has been great interest in evaluating multiple plant extracts to prevent or treat FLHS.

FLHS has also been adopted as a study model for the human condition called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), also referred to as metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

This boom in biomedical research using laying hens suffering from FLHS may help create new efficacious solutions for this poultry disease. We encourage readers to be attentive to these reports and validate the proposed solutions in their layer flocks.