07 Jan 2020

Interactions. Infectious anemia virus and Avian infectious bronchitis

Se debe considerar la posible interacción entre el Virus Anemia infecciosa (CAV) y la Bronquitis Infecciosa Aviar (IBV), para aminorar las pérdidas económicas.

Available in other languages:

Content available at:

Español (Spanish)

These complexes often begin with a subclinical immunosuppressive agent that gives the gateway to a clinical viral infection, often respiratory. Subsequently, if the clinical condition is not detected quickly, bacterial contamination occurs.

“The possible interaction of CAV and IBV viruses with practical analysis to reduce losses should be considered”.

When clinical signs occur, it must be borne in mind that it may be a “complex” with etiological factors that are not so obvious, but must be prevented in order to control the pathology.

In economic terms, it would often seem inefficient to control diseases that do not really induce obvious clinical conditions, such as subclinical avian infectious anemia (CAV) or infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) and it is difficult to economically justify measures that reduce subclinical effects.

Traditionally, what is done is to implement vaccinations to try to prevent clinical conditions, but little or nothing is done in terms of evaluations of the level of antibodies against IBDV or CAV or of lymphocyte integrity in the bursa of Fabricius or thymus.

If this is not done, it is very unlikely that the vaccination strategy used will have positive effects and often subclinical immunodeficiency conditions continue to occur without being detected.

In order to analyze this problem, the possible interaction of CAV and avian infectious bronchitis (IBV) viruses should be considered, with a practical analysis to be able to reduce the losses caused by the interaction of these pathogens.

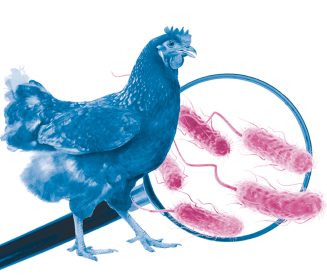

INFECTIOUS BRONCHITIS

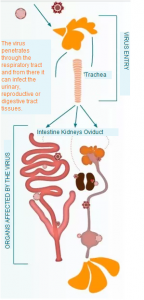

Figure 1. Diagram depicting the pathophysiology of avian infectious bronchitis.

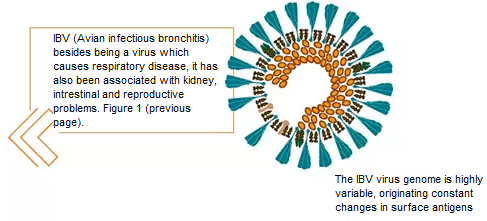

IBV (avian infectious bronchitis) is a RNA-enveloped virus that is part of the Coronaviridae family, genus Nidovirales. It is probably one of the endemic viruses that cause some of the biggest losses for the global poultry industry.

The losses in the production and reduction of the quality of eggs, problems of food conversion and seizures in the processing plant are part of the most important effects on productive parameters.

The genome of this virus is highly variable, which causes constant changes in the surface antigens of the virus. This is why it has dozens of sero / genotypes, which makes its control and prevention very difficult since there is no complete cross protection between serotypes or variants.

In addition to the existence of different serotypes, variants can also be found. These variants are specific to each geographical location and depending on their variability, their control and prevention can be difficult.

Figure 2. Effects of Infectious Bronchitis Virus

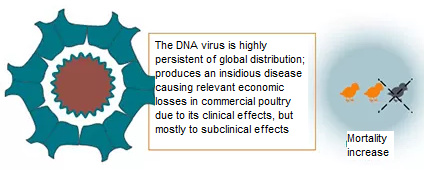

INFECTIOUS ANEMIA

Avian infectious anemia is caused by a non-enveloped DNA virus of the family Circoviridae genus Gyrovirus.

Losses caused by this pathology, which clinically affects chicks between 2 and 4 weeks, are associated with an increase in mortality, poor performance, lower uniformity and greater seizures in the slaughter plant.

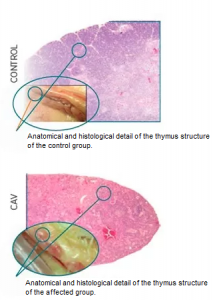

The basis of subclinical presentation is immunosuppression caused by lymphocyte depletion that is widespread, but with more severe effects on the thymus of affected birds Figure 4.

Figure 4. Severe lymphocyte depletion and thymus atrophy in chickens experimentally challenged with the infectious anemia virus CAV), compared to a control group CONTROL).

Immunodeficiency caused by CAV has been associated with:

The presentation or increased severity of hepatitis by inclusion bodies

Coccidiosis

Gangrenous Dermatitis

Infectious bursal disease

Avian infectious bronchitis (Toro et al., 2000, 2006, 2009).

Studies conducted at the University of Auburn in Alabama using commercial chickens have shown that some outbreaks of respiratory diseases specifically caused by IBV are often associated with lymphocyte depletion (Hagood et al., 2000).

A second study demonstrated epidemiological evidence of the coexistence of immunodeficiency caused by CAV and / or IBDV in birds presenting IBV (Toro et al., 2006).

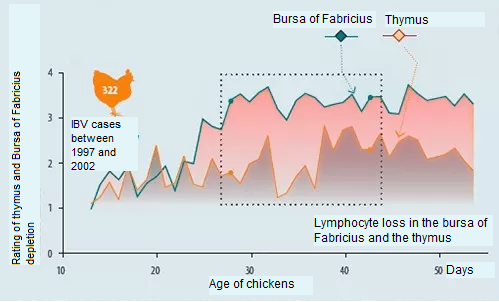

Broilers sent to the diagnostic laboratory for respiratory problems (322 cases from 1997 to 2002) showed a high correlation between isolation of IBV and a reduced number of lymphocytes, both in the bursa of Fabricius and in the thymus, white organs for IBDV and CAV, respectively (Graph 1).

The increase in histopathology rating due to lymphocyte depletion in thymus between days 30 and 40 of age coincides with IBV isolates in the laboratory, which showed an increase between days 27 and 43 of age of broiler chickens.

These problems usually manifest clinically as:

- Airsacculitis detected in the processing plant.

- Increasing seizures.

- Economic losses for the producer.

In an analysis of broilers seized due to septicemia-toxemia in the slaughterhouse, atrophy of the bursa of Fabricius and thymus accompanied by atrophy and aplasia of the bone marrow were found.

These results suggest the existence of immunosuppressive diseases of the CAV or IBDV type in chickens seized in slaughter plants (Hoerr., 2004).

Graph 1. Rating of lymphocyte depletion based on the histopathology of the Bursa of Fabricius and the thymus in 322 clinical cases of broilers diagnosed with IBV and respiratory signs in the state of Alabama, USA (Toro el al., 2006)

Thymus

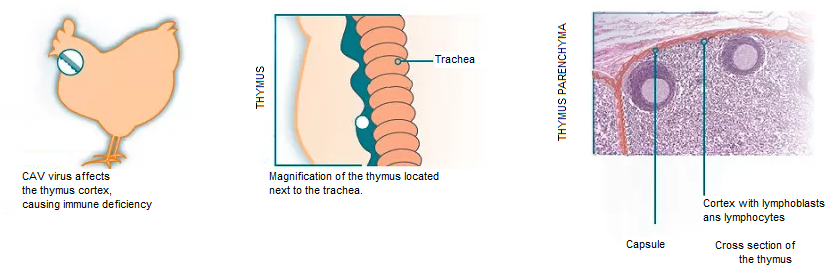

If we focus on the possible interaction of CAV and IBV we should consider the white organ for CAV, which is the thymus.

CAV affects lymphoblasts located in the thymus cortex, causing an immunodeficiency associated with T lymphocytes.

T lymphocytes are responsible for cytotoxic responses (destroying virus-infected cells such as IBV) that are relevant for virus clearance (Collison et al., 2000).

Mucosa

On the other hand, CAV has also been shown to reduce the local immune response in the mucous membranes (van Ginkel et al., 2008), which is important to eliminate the IBV virus in the nasal, ocular, etc. mucous membranes.

Innate response

As if this were not enough, CAV also affects the innate (nonspecific) response by limiting the destruction of the virus in the bird’s organism.

Therefore, it is very important to have a good control strategy for the CAV virus, since in the case of IBV infection the respiratory clinical signology is greater and its persistence in the lot is longer (Toro et al., 2006).

Moreover, being concomitant CAV and IBV infections common in broilers and taking into account basic studies on IBV and its variation we can point out that it is very likely that these coinfections contribute to the emergence and establishment of new sero / genotypes of IBV ( Gallardo et al., 2016).

Figure 5. Enlargement and localization process of lymphoblasts found in the thymus cortex

One of the problems caused by natural exposure is the lack of uniformity of the response in the breeding lots. In CAV, a single breeder with low antibody levels is sufficient for the virus to be transmitted vertically, potentially affecting the rest of the chickens due to horizontal transmission.

Taking into consideration the above, the vaccination of the lots of breeders is really the way to go. In addition, it is very important and economically profitable to investigate and understand the response of breeding flocks to vaccination or exposure against immunosuppressive viruses, including CAV, in order to understand the effect of subclinical conditions of respiratory disorders in commercial birds.

This can be done by combining histomorphometry and histopathology studies in the Bursa of Fabricius and the thymus along with the evaluation of ELISA antibody titers against diseases such as CAV and IBDV.

CONCLUSION

Many of the pathologies in poultry farming are presented in the form of complexes, involving immunosuppressive diseases and respiratory viruses. An example of these complexes are infections caused by CAV and IBV.

This synergy has been documented in systematic research and in retrospective epidemiological studies. Immunosuppression caused by CAV is able to reduce specific and nonspecific responses against IBV virus and possibly other respiratory viruses.