Content available at: Español (Spanish)

A study was recently carried out in commercial broiler farms, which examined the water consumption of chicks during their first seven days.

High-precision ultrasonic water meters were installed in twenty-two broiler houses (eighteen houses measuring 152 meters by 12.2 meters and four houses measuring 152 meters by 16.5 meters) in nine farms.

- The water meters are capable of accurately measuring water flow rates of 0.02 liters / min, which is 50 times less than the flow rate measured by the water meters commonly used in poultry farms.

- The meters were sensitive enough to measure, minute by minute, water consumption from the moment the chicks were unloaded into the house.

This study showed that water consumption is closely related to food consumption.

- During the first week, the chicks drank approximately 113.6 liters of water for every 45.4 kilos of feed consumed (editor’s note: water / weight ratio = 2.5 times) (Alqhtani, 2016).

- The high precision of the water meters allowed to see patterns in the water consumption of the chicks, and therefore in the feed consumption, that are not seen with conventional water meters.

One of the most interesting patterns discovered is that even when given continuous light, birds have a marked circadian life cycle (24 hours) during rearing.

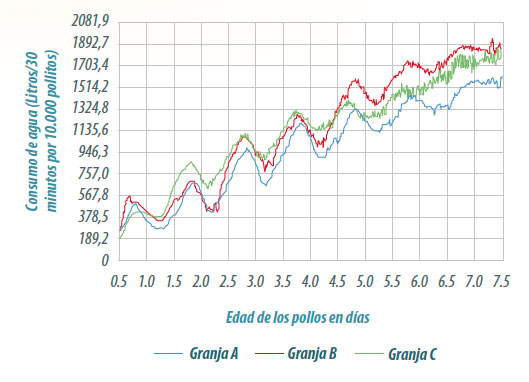

- The day after the chicks were placed in the house, there was approximately double the water / feed consumption during the “day” than the next “night” (Figure 1).

- The pattern becomes less apparent as the week progresses.

- By the seventh day, there is generally less than 20% difference between “day” and “night.”

- Let us bear in mind that only totally enclosed warehouses were used in the study; so the amount of outside light the birds were exposed to was minimal, if any.

Figure 1. Circadian rhythm of water use in chick flocks (Week 1)

THE CHICKS HAVE AN INTERNAL CLOCK

This internal chick clock determines the activity level of the bird throughout the day by establishing a “day” and a “night”.

This clock is “set” in the hatchers when a chick breaks the shell or even when it is still in the egg, depending on how much light is in the hatcher.

Although the most important factor in the setting of this chick’s internal clock is light, there are other factors that can also affect it (sound, service time, house temperature, etc).

The fact is that, with chicks and also with older birds, even if we provide continuous light in a house, the activity of the birds will always tend to establish a 24-hour cycle (figure 1).

- In the farms studied, the 24-hour cycle of activity decreased during the first week of life, possibly because there was no strong “signal” to keep all chicks in sync.

- In nature, sunrise and sunset unify all the birds in a flock at the same time. The same is true when there is a lighting program where the lights are turned on and off at the same time each day.

- But, it appears that providing 24 hours of light can cause each chick’s individual clock to deviate from the overall flock clock. This is known as “free cycling.” The longer the chicks are in continuous light, the weaker the activity cycle of the flock.

- The individual chicks are likely to remain on a day cycle of approximately 24 hours.

- The problem is that not all chicks may be on the same 24-hour day cycle.

TO CONTINUE READING REGISTER IT IS COMPLETELY FREE Access to articles in PDF

Keep up to date with our newsletters

Receive the magazine for free in digital version REGISTRATION ACCESS

YOUR ACCOUNT LOGIN Lost your password?